The COVID-19 pandemic has evoked in me a flurry of emotions ranging from sadness to frustration to outright rage. I’ve even had moments of immense gratitude. Now that we’ve surpassed 100,000 deaths in the U.S. alone (see here for up-to-date statistics), memories of loved ones who have passed away have started to surface.

Most recently, one of my uncles, who fell in his hospital room and never recovered. My grandmothers — one a Buddhist/Shinto who also hung paintings of Christ in her home (just in case?), the other a devout Jehovah’s Witness. My grandfather, who passed away in a nursing home. A high school friend, who succumbed to kidney cancer in her 30’s. Another friend, who hung from a third story window and let go.

The death that stands out the most, though, is my father’s. He was diagnosed with stage 2 bladder cancer in 2010. Standard of care was removal of the bladder followed by radiation therapy, but he would have to fly from Honolulu to Los Angeles if he wanted a surgical procedure that wouldn’t leave him with a urostomy pouch… and he didn’t want to be separated from my mom. He opted for radiation therapy only. A year later his cancer had metastasized, and his health deteriorated rapidly. We brought him home to live out his final weeks.

The hospice nurses warned us that he was a “stoic patient” and would not let us know if he was in discomfort or pain. They also told us that people often know when they are near death, and they would often (involuntarily) show an uptick in health and energy shortly before dying — a last-ditch effort by the body to stay alive. How cruel of nature to pump optimism into a desperate situation.

There are three moments that seem to come up again and again when I look back on his death.

Moment 1: My dad had a J-tube, through which we would feed him and administer medication, including morphine. One night, with my mom and two brothers in the room, he waved away the morphine. “I’m fine!” he declared, trying to spare us from emotional pain. But he was clearly in pain. I leaned in closer to him, vial of morphine in hand. I pursed my lips and looked him in the eyes. He nodded slightly. I administered the morphine discreetly.

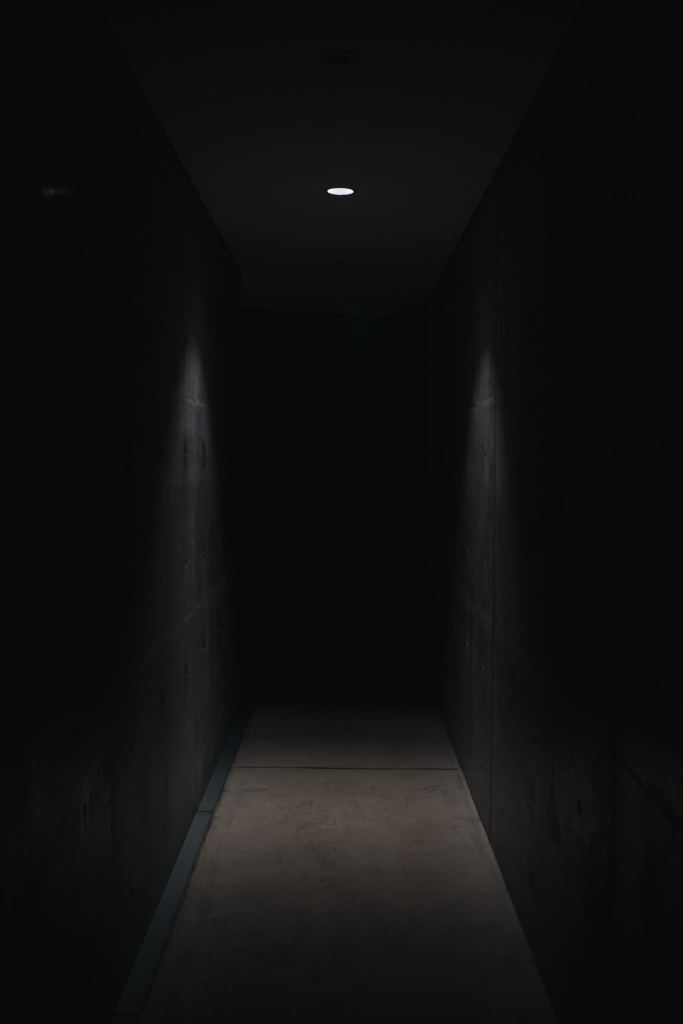

Moment 2: A few days later, he gathered everyone around him, telling us with great despair that he couldn’t “see the light.” The whites of his eyes were yellow from jaundice and his vision was severely impaired. He was telling us “goodbye” while we all fought back tears, trying to reassure him that his time had not yet come. But he knew better.

Moment 3: Early the next morning, my older brother came to my bed and whispered, “Dad passed away in his sleep.” “Fuck.” That’s all I could say. I was in such denial that when the morgue sent us a photo of my dad to confirm his identity before cremating him, I had a pang of fear that he might be incinerated alive.

In Japan, it is said that if you pass away in your sleep it means you lived a good life. My dad certainly wasn’t perfect, but he did his best. As I write this post, horrible memories surface as well as beautiful ones. I remember at age 5 watching my dad push my older brother into the refrigerator, punching and screaming at him, rage in my father’s eyes and tears in my brother’s. Terrified and perhaps grasping for normalcy, I remember asking someone (I can’t even remember who — my mom? My grandmother?) for more milk as I held up my plastic pink Kiki and Lala mug. Several years later my brother would be forced to join the Army and would have almost no contact with my dad until he was on his deathbed. I later learned that my dad was also abused, by both his father and his alcoholic step-father after that. I remember my dad telling me he wasn’t going to attend my high school graduation (I was class valedictorian) because it “wasn’t a big deal.” He did end up coming. I remember learning how to play “Unchained Melody” (one of his favorite songs) on the piano as part of a gig I had playing background music at a fancy Sunday brunch in Tokyo, and how my dad told me not to bother because it wasn’t going to go well anyway.

These experiences are in such contrast to others… like the immense patience he showed when helping me with my algebra homework. I was in the 7th grade and desperate to prove to the older students that I belonged. He’d sit with me every night, never making me feel bad if I didn’t understand something. I ended up with one of the highest grades in the class. When my older son (A1) was two months old, he stayed with me for over a month to care for him while A1’s dad was off in India. He absolutely adored his grandson. He had no problem literally cradling him for an entire day. And I knew he understood when I’d come home from work, moody and exhausted, needing time to myself before taking over baby duties. Before he died, he told me he was in fact very proud of me, but wanted me to be humble. He grew up in a home with dirt floors. Dirt. Floors. He was incredibly smart, but extremely humble. He worked hard to provide for his family all of the things he never had – and much, much more.

When he was told his cancer had spread, he wanted to do anything and everything he could to prolong his life. But he had few options at that point. Nearly 10 years later I still carry a copy of his medical records with me, documentation of his year-long battle and everything he endured. I will likely carry it with me for the rest of my life. Just as I will my memories of him.