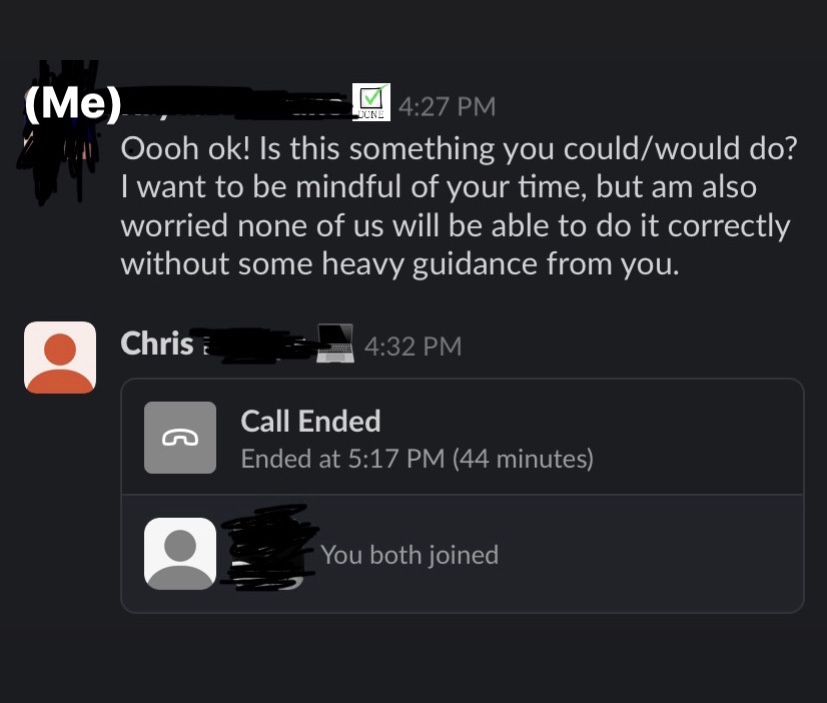

Chris calling me, after I expressed needing his expertise on a project, perfectly captures the kind of relationship we had. I looked up to him, and he graciously offered his help whenever I needed it.

Our relationship didn’t start out on the best footing to be honest. It was maybe my second week at this new job (nearly five years ago), and I sent a group email that included him, expressing interest in utilizing the medical encounter data we have access to. Chris replied all, questioning my ability to use these data appropriately. I worried I had stepped on toes, and was quickly reassured by a number of people that I had not — Chris was just a difficult person. So difficult, in fact, that one of our coworkers had tried to get him fired a number of years prior.

Me being me, needing approval from everyone, especially authority figures, made it my mission to get on Chris’ good side. I started to compliment him by asking for his guidance — often. I looked for common interests (it wasn’t hard… we’re both epidemiologists… obviously we love data and coding). I’d try to nerd out with him. Then one day I discovered what has become my favorite SAS procedure: PROC EXPAND. It’s a relatively obscure procedure but oh so glorious when working with medical encounter data. Chris agreed. He encouraged me to submit an abstract to a regional SAS conference describing its utility (I did, and even won an award for it). I had his approval.

Over the years I would consult him when I had questions about medical encounter or pharmacy data. He’d offer me snacks, I’d bring him chocolate. Last fall, I found an opportunity to work with him directly. We decided to co-lead a vaccine study proposal. The last time we met in person was just before I went on maternity leave. We had a meeting with our military collaborator, who Chris greatly admired, to plan our study approach, though there was a good amount of banter too. Over the next few days Chris ran preliminary analyses for me, and sent a million different things for me to consider as I finished writing our proposal.

It didn’t get funded. But at the end of that 45-minute call (photo for this post), Chris suggested we resubmit the proposal to some other agency. In so many words, he expressed how much he loved my research and thought I had written a very strong proposal — it’s just that the funding agency didn’t get the budget they thought they would. He was trying to make me feel better about the rejection. “It’s not you, it’s them.” I had his approval.

Chris reminded me of my dad. A bit abrasive, geeky, a food lover, and very set in his ways. He was surprisingly endearing — you just needed to get past his rough exterior. He was an Air Force veteran, and the PI for a study of Marine recruits (turns out my husband took his survey in 2016, long before we met). Having his approval was healing. It was like getting the approval my dad never expressed.

I don’t know yet the nature of his death, so I feel my grief is a bit stunted. Did his mental health suffer due to the isolating effects of the pandemic? Or did he die of “natural” causes? Either way, he died alone, which kills me to think about. Nobody should ever have to die alone. Since his death was announced, colleagues have posted stories about Chris and the things they appreciated about him, which has helped my grieving process. Still, I don’t think I’ve quite processed everything yet. And maybe I won’t until I see an obituary, or attend his funeral (if there is one — yet another consequence of this pandemic)…

I went back to our Slack messages to reminisce a little and noticed he still has his status set to “working.” If there is an afterlife, I’d like to think that he is happily coding away, immersed in data, and eating some fine chocolate.